- Home

- Grace Coddington

Grace

Grace Read online

Michael Roberts, Sally Singer, Susie Menkes, Fuanca Sozzani, Tabitha Simmons, Camilla Nickerson, Elissa Santisi

Phyllis Posnick, Hamish Bowles, Virginia Smith, Andre Leon Talley, Anna Wintour, me, Tonne Goodman, Mark Holgar

Copyright © 2012 by Grace Coddington

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Random House and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Coddington, Grace.

Grace:a memoir/Grace Coddington.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-679-64521-4

1. Coddington, Grace, 1941– 2. Image consultants—Great Britain—Biography. 3. Fashion editors—Great Britain—Biography. 4. Models—Great Britain—Biography. 5. Vogue. I. Title.

TT505.C63A3 2012

646.70092—dc23

[B] 2012021216

www.atrandom.com

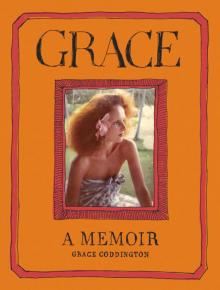

Cover design and illustration: Grace Coddington

Cover photograph: © Norman Parkinson Ltd./courtesy Norman Parkinson Archive

Book design by Grace Coddington and Michael Roberts

Drawings by Grace Coddington

v3.1

For Henri

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

INTRODUCTION

I ON GROWING UP

II ON MODELING

III ON THE FASHIONABLE LIFE

IV ON BRITISH VOGUE

V ON TAKING PICTURES

VI ON BEGINNINGS AND ENDS

VII ON CAFÉ SOCIETY

VIII ON STATES OF GRACE

IX ON BRUCE

X ON DIDIER

XI ON CALVINISM

XII ON AMERICAN VOGUE

XIII ON THE BIGGER PICTURE

XIV ON ANNA

XV ON PUSHING AHEAD

XVI ON LIZ

XVII ON BEAUTY

XVIII ON CATS

XIX ON THEN AND NOW

Selected Work

Information

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Contributors

Other Books by This Author

GALLERY

Me, the chubby-cheeked future model, aged four or five

One of many, many hairstyles, about 1954

My first model card, with the picture Vogue loved, 1959

My famous Vidal Sassoon Five Point Cut. Photo: David Montgomery, 1964

My very happening makeup look. Photo: Jeanloup Sieff, 1966. © Estate of Jeanloup Sieff

Guest-modeling in a YSL fashion show, Maunkberry’s nightclub, London. Photo: Anthony Crickmay, 1970. Courtesy of Vogue © The Condé Nast Publications Ltd.

On a shoot inspired by Edward Weston, Bellport, Long Island. Photo: Bruce Weber, 1982

Photographers gather to celebrate my book Grace: Thirty Years of Fashion at Vogue. From left to right: Mario Testino, Sheila Metzner (lying down), Ellen von Unwerth, Steven Klein, Annie Leibovitz, Alex Chatelain, Herb Ritts (seated), Bruce Weber, Craig McDean (on wall), Arthur Elgort, me, David Bailey, Peter Lindbergh. Photo: Annie Leibovitz, 2002

Never thinner: My portrait with a borrowed cat for Italian Vogue. Photo: Steven Meisel, 1992

Peering into the future, London. Photo: Willie Christie, 1974

With Didier at a Vogue party, New York Public Library. Photo: Marina Schiano, 1992

INTRODUCTION

In which

our heroine

finds fame

on film but, like

Greta Garbo,

just wishes to be

left alone.

The first I heard of The September Issue (the movie that is the only reason anyone has ever heard of me) was when Anna Wintour called me into her office at Vogue to tell me about it and said, “Oh, by the way, I’ve agreed to a film crew coming in to make a documentary about us.” The film was originally supposed to be about organizing the ball at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute, but it grew bigger and bigger. Now they would be turning up to film all the discussions, meetings, fights, and frustrations that go into creating the most important issue of the year. They would be in our office, and on our sittings, too. It was just about everything I didn’t want to hear. As creative director of the magazine, I have a thousand things to deal with. And it’s difficult enough putting a complicated photo session together without having onlookers hanging around! “Don’t expect me to be in it,” I said, sensing Anna’s eyes glaze over as she looked past me out the window. She has a way of blanking people out when they are saying something she doesn’t care to hear.

My reaction to this intrusive idea was naturally one of horror, because my feeling has always been that people should concentrate on their jobs and not all this fashionable “I want to be a celebrity” shit. Afterward I found out that it had taken the filmmakers almost a year to persuade Anna to say yes. I’m sure she agreed in the end only because she wanted to show that Vogue is not just a load of airheads spouting rubbish. By then we had all had enough of The Devil Wears Prada, with its portrayal of fashion as utterly ridiculous.

During filming, the crew approached me time and again, confident they could win my cooperation. They had heard that I could be difficult (and I did have a reputation for refusing interviews), yet still they knocked at my door requesting my participation. Perfectly nice they were, but I told them I wasn’t interested and I didn’t want them anywhere near me because it was too distracting. I hate having people observing me; I want to swat them away like a swarm of flies.

My office door remained firmly closed. I said the rudest things to the director, R. J. Cutler, and for about six months managed to keep him and his crew at bay whenever they pointed a camera in my direction. They would be filming among the racks of clothes in the hallway outside my office, and I could hear people saying things like “Ooh, I just love this red dress,” and “Ooh yes, I think Anna would definitely like it,” and all the kinds of superficial nonsense people come out with in front of the cameras. Then the film crew followed us all the way to the Paris collections. This was really exasperating. They were constantly getting in our way or elbowing past us to get a shot of Anna. At the Dior show, Bob the cameraman trod on my toe as he filmed her while walking backward. That was the final straw. I really let him have it. “By the way,” I screamed, “I work at Vogue, too!” They were so intent on filming Anna’s every move: sitting in the front row, watching the show, reacting to the show. It all seemed so over-the-top. I noticed that she was even wearing a mike, which of course created yet another obstacle, because now she would only talk to me in a guarded sort of manner.

“The September Issue” film cover

“I’m really not interested”

“I don’t want you hanging around anywhere near me … …”

Eventually I thought, “If you can’t beat them, join them.” Besides, Anna had hauled me into her office one last time and told me, “They really are coming to film your shoot. They are going to film your run-through, and this time you cannot get out of it. There will be no discussion.” So I definitely had a gun to my head. “But if you put me in that movie, you will hear things you won’t like,” I warned. “I can’t pretend. I’ll be so focused on the shoot that I will probably blurt out anything that comes to mind.” (What I secretly thought was that if I said anything too bad, they wouldn’t use it —which is why I’m caught swearing like a trooper throughout the entire movie.) There had been other documentaries about the fashion business that I’d been filmed for, but my contributions had always ended up on the cutting room floor.

When

I saw the final cut for the first time, I was in total shock. There was way too much of me in the film. Later, one of the crew members told me that the forceful dynamic between Anna and me strengthened the movie. We had two screenings at Vogue. I think Anna didn’t want to see it with the rest of us. I was down to go to the first showing with the fashion people; she was off to the second with the writers and the more intellectual crowd, whose opinion she probably valued more. Our hearts sank as we tried to remember what was said during all those months of filming because the whole thing had been out of sight ever since, stuck in the editing room for almost a year.

Now I can look at the end result and laugh. After all, I was rather outspoken. Nevertheless, there really is way too much of me. Once Anna had seen the finished version, I never got an opinion out of her about it. Ever. All I know is that she didn’t disapprove, but she didn’t entirely approve of it, either. The only thing she said was “Just let Grace do all the press,” and then moved on. She did, however, attend the first major showing at the Sundance Film Festival and stood onstage afterward at the Q and A, unmoving and enigmatic in dark glasses and clutching a bottle of water while R.J. did most of the talking.

At a screening I attended in Savannah—it was the first time I agreed to do some publicity—with Vogue’s editor-at-large André Leon Talley, there was an extensive Q and A session with a roomful of journalists who kept saying, “Oh, we think you are so wonderful.” So I grew to like that. (I’m kidding, but it was quite pleasant.) Throughout the question time, the audience was mostly trying to find out about Anna. (They are always trying to find out about Anna.) André was brilliant. He’s very good at deflecting awkward moments. Whenever she was mentioned, he changed the subject and began referring instead to Michelle Obama or Diana Vreeland.

I’m always surprised that people who’ve seen the movie respond to me in such a positive manner. Maybe it’s because I come across on-screen as so emotional. It makes me appear idealistic, in contrast to Anna, who is by nature much more determinedly and quietly controlled. Or maybe it’s because I appear to be put upon. Or perhaps they are always going to react to someone who seems to be spontaneous. Or someone who dares talk back to her boss like no one else does at the magazine, as I have done and probably will again.

During the opening weeks of the film I was also asked to give a talk at the New York Public Library by Jay Fielden, who at the time was editor in chief of Men’s Vogue. This was a particularly nerve-wracking situation because, out of the corner of my eye, I could see Anna and S. I. Newhouse, the owner of Condé Nast, sitting in the audience. After a while, the Q and A’s became much easier. I got into the rhythm of things, hiding in the dark until the last minute—at which point you make your sudden dramatic appearance—and looking directly at the questioner. And then one day I realized I had somehow become pretty recognizable. I found groups of people regularly gathered in front of my apartment building in Chelsea, New York: fashion freaks, gays, straights, young, old, a whole mixture. It was a cross section of the neighborhood, all shouting at me from across the street—but always in such a nice way. I felt like the Beatles. Actually, better than the Beatles, because the crowds chasing them in the early days of their fame could get rough. I did once get mobbed, though. Having agreed to do a Q and A at my local cinema, I arrived right as the audience from an earlier showing was leaving. When I rounded the corner, all I could hear was “Grace, Grace. Oh my God, it’s her!”

“Look Nicolas, he thinks we’re Brad & Angelina”

And they still haven’t forgotten. Perhaps it’s because I’m frequently on the street or in the subway and not discreetly hidden away in a Town Car, like Anna. It got me thinking, now that my memories had been well and truly raked up by all the questions I’d been asked, that maybe I had a bigger story to share. Which led to the next surprise—here I am doing something I never imagined I’d be old or interesting enough to embark on: writing my memoirs.

Sometime after The September Issue came out, I was having a quiet dinner in a little restaurant in Lower Manhattan with Nicolas Ghesquière, the designer for Balenciaga, who had flown over from Paris. “Grace, is it true that people recognize you wherever you go?” he asked me suddenly. So when we finished eating, I suggested he walk home with me. And as we strolled past the many crowded restaurants, bars, and gay nightclubs in my part of town, people kept popping out, saying, “It’s Grace. It’s Grace! Wow—and Nicolas Ghesquière, too.” Cell phone cameras flashed and clicked. In the end we just cracked up, the both of us behaving like Paris Hilton!

I

ON

GROWING UP

In which

the winds howl,

the waves

crash, the rain

pours down,

and our lonely

heroine dreams

of being

Audrey Hepburn.

There were sand dunes in the distance and rugged monochrome cliffs strung out along the coast. And druid circles. And hardly any trees. And bleakness. Although it was bleak, I saw beauty in its bleakness. There was a nice beach, and I had a little sailboat called Argo that I used to drift about in for hours in grand seclusion when it was not tethered to a small rock in a horseshoe-shaped cove called Tre-Arddur Bay. I was fifteen then, my head filled with romantic fantasies, some fueled by the mystic spirit of Anglesey, the thinly populated island off the fogbound northern coast of Wales where I was born and raised; some by the dilapidated cinema I visited each Saturday afternoon in the underwhelming coastal town of Holyhead, a threepenny bus ride away, where the boats took off across the Irish Sea for Dublin and the Irish passengers seemed never short of a drink. Or two. Or three or four.

“Well, it could be summer or winter, but either way we’re not swimming”

For my first eighteen years, the Tre-Arddur Bay Hotel, run by my family, was my only home, a plain building with whitewashed walls and a sturdy gray slate roof, long and low, with the understated air of an elongated bungalow. This forty-two-room getaway spot of quiet charm was appreciated mostly by holidaymakers who liked to sail, go fishing, or take long, bracing cliff-top walks rather than roast themselves on a sunny beach. It was not overendowed with entertainment facilities, either. No television. No room service. And in most cases, not even the luxury of an en suite bathroom with toilet, although generously sized white china chamber pots were provided beneath each guest bed, and some rooms—the deluxe versions—contained a washbasin. A lineup of three to four standard bathrooms provided everyone else’s washing facilities. For the entire hotel there was a single chambermaid, Mrs. Griffiths, a sweet little old lady in a black dress and white apron equipped with a duster and a carpet sweeper. I remember my mother being quite taken aback by a guest who took a bath and rang the bell for the maid to set about cleaning the tub. Why wouldn’t the visitors scrub it out themselves after use? she wondered.

Our little hotel had three lounges, each decorated throughout in an incongruous mix of the homely and the grand, the most imposing items originating from my father’s ancestral home in the Midlands. At an early age, I discovered that the Coddingtons of Bennetston Hall, the family seat in Derbyshire, had an impressive history that included at least two wealthy Members of Parliament, my grandfather and great-grandfather, and stretched back sufficiently into the past to come complete with an ancient family crest—a dragon with flames shooting out of its mouth—and a family motto, “Nil Desperandum” (Never Despair). And so, although some communal rooms remained modest and simple, the dining room was furnished with huge, inherited antique wooden sideboards decorated with carved pheasants, ducks, and grapes, and the Blue Room contained a satinwood writing desk hand-painted with cherubs. A large library holding hundreds of beautiful leather-bound books housed many display drawers of seashells, and various species of butterfly and beetle. There was a grand piano in the music room (from my mother’s side of the family), and paintings in gilded frames—dark family portraits—hanging everywhere else.

Gue

sts would rise with the sun and retire to bed at nightfall. If they needed to use the telephone, there was a public booth in the bar. There was a single lunchtime sitting at one o’clock and another at seven p.m. for dinner, with only two waiters to serve on each occasion. Tea was upon request. Breakfast was served between nine and nine-thirty in the dining room—and certainly never in the bedroom. There was also a games room with a Ping-Pong table where I practiced and practiced. I was good. Very good. I would beat all the guests, which didn’t go down too well with my parents.

The sand on the long, damp beige ribbon of beach in front of the hotel was reasonably fine-grained but did get a bit pebbly as you approached the icy Irish Sea slapping against the shore. You could, however, paddle out for a fair distance before it became freezingly knee-deep.

Throughout my childhood I longed for the lushness of trees. Barely one broke the rocky surface on our side of the island. Only when we paid the occasional family visit to my father’s aunt Alice in her big, shaded house on the south side would we ever see them in numbers. My great-aunt was extremely frail and old, so I always think of her as being about a hundred. Her home was close to the small town of Beaumaris, which had a huge social life in the 1930s. My parents met there, as my mother lived nearby with her family in a sprawling house called Trecastle.

Flanking our hotel on one side was a gray seascape of cliffs, rocks, and bulrushes, then acres of windswept country and a lobster fisherman’s dwelling, and on the other Tre-Arddur House, a prestigious prep school for boys. Once I reached the age when boys became of interest, I used to linger shyly, watching them play football or cricket beyond the gray flinty stone wall bordering their playing fields until I arrived at the bus stop and took off on my winding journey to school.

Grace

Grace